Spotting and avoiding Scale Extrapolation Errors

How smart technologists often delude themselves

Introduction: space datacentres as the trigger

The other day I wrote a fairly pithy LinkedIn post about space datacentres and why they are a great example of what I’m calling a “scale extrapolation error”.

This article expands on the general definitions and causes of that error class.

The LI post pointed out that coming up with a (potentially good) way to scale one variable or input for a complex sector does not mean that all the other necessary inputs or variables also scale.

Just because solar energy is cheap in space and it’s suddenly possible to deploy hundreds or thousands of satellites does not mean that it’s a substitute for terrestrial hyperscale DCs for cloud or AI use. They also need cooling, connectivity, maintenance, interconnection, developer support, low latency, reliability, regulatory oversight and much more.

Furthermore, today there aren’t even proper prototypes or proof-of-concepts, let alone any clear demonstrations that scaling to megawatts or gigawatts can be achieved as easily as Powerpoints or AI-generated animated videos suggest.

I also cited a number of other scale extrapolation errors I commonly see asserted in telecoms and adjacent cloud/IT domains:

- The belief that terresrial edge computing nodes can replace hyperscale DCs

- The idea that satellite D2D (direct-to-device, or sometimes direct-to-cell) can replace terrestrial mobile networks

- Hype that 5G-based (or, again, satellite) FWA fixed wireless access can replace massmarket fibre broadband (FTTH)

- Assorted visions that 5G can replace Wi-Fi for indoor or local nework connecivity (or, more rarely, vice-versa)

All of these are examples of scale extrapolation, assuming a technology or business model that you observe at one level can scale smoothly (linearly or exponentially), up or down, while ignoring thresholds, multi-variable optimisation, and non-linear constraints.

In reality, a system’s performance, risk, economics, controllability and governance will move through different “regimes”, which alter the way in which scaling works.

Scale curves are never smooth.

The more general scaling extrapolation delusion

While the focus of the space datacentre post is on substitutional scale - tech X will replace tech Y, as it’s got an advantage with variable A - that is not the only way this error-class manifests in telecoms and cloud sectors.

It’s actually a family of errors, which manifest in a variety of ways for whole industries or individual companies or products:

Scale up organically - more of the same

Scale up and substitute - as described here about space DCs

Scale down organically - the same, but for niches

Scale down and substitute - fragment / decentralise

Sometimes the fallacy lies in extrapolation of an existing solution’s market adoption, irrespective of whether it has alternatives. It might just run out of steam, or face obstacles in either supply or demand.

Or there could be obstacles to a specific company’s organic growth and scale, driven by business or operational model constraints - or just management’s execution ability.

The net result is the same - what sounds like a promising concept or service has some hard limits to its adoption or applicability. The hype needs to be questioned.

What causes a “scale extrapolation error”

There are some common underlying reasons and dynamics in play here. A scale extrapolation error is when you assume scaling is smooth (linear or exponential) from a small base, while ignoring:

thresholds: regime changes where the problem becomes different

multi-variable optimisation: real systems must satisfy many constraints simultaneously

new coupling effects: interactions that don’t exist at small size

non-scaling costs/risks: fixed costs, compliance, tail risks, reliability requirements

ecosystem inertia: tools, skills, standards, supply chains, distribution

behavioural factors: buyer perceptions, exclusivity, branding

The error often hides behind an innocent-looking move: taking a local trend and projecting it globally.

While everyone is familiar with the concept of “economies of scale”, few really bother to assess when it applies, and how that principle could face friction in the real world. In particular, an economic and business concept that originally applied just to manufacturing does not necessarily translate to the delivery of services or creation of infrastructure.

Why it feels reasonable

Scale extrapolation is often seductive, because early progress for a company or sector is often real:

prototypes or lab-tests work well

unit costs or capacity expansion fall initially, for instance for the first few doublings of market size

early adopter customers are forgiving of problems and limitations

pilots and first-generation products avoid the nastiest edge cases

But then the cliffs start to arrive...

Linear brain in a non-linear world: humans underestimate thresholds.

Single-variable storytelling: one “killer advantage” is easier to articulate (or post about on LinkedIn) than a system model.

Demo dependency: if it works once, people treat scaling as merely “execution.”

Survivorship bias: we selectively remember the handful of technologies that scaled cleanly and forget the graveyard of failures.

New stakeholders: Competitors, regulators and policymakers rarely care about small innovations. But they wake up as things scale. This is true of fanboys and trolls as well.

The problem is that some companies - and investors - see hype as an important part of the narrative, even if they don’t really believe all of it.

Funding, policy, and internal budgets often require a replacement story or a huge addressable market.

“Hybrid coexistence with a 8% market share” doesn’t raise money, pump valuations or win headlines.

There’s a belief in “fake it until you make it” and the idea that it’s possible to create self-fulfilling outcomes.

That means that as well as actual errors, another style of scale-extrapolation is rhetorical. It’s basically an economics-of-attention hack masquerading as forecasting.

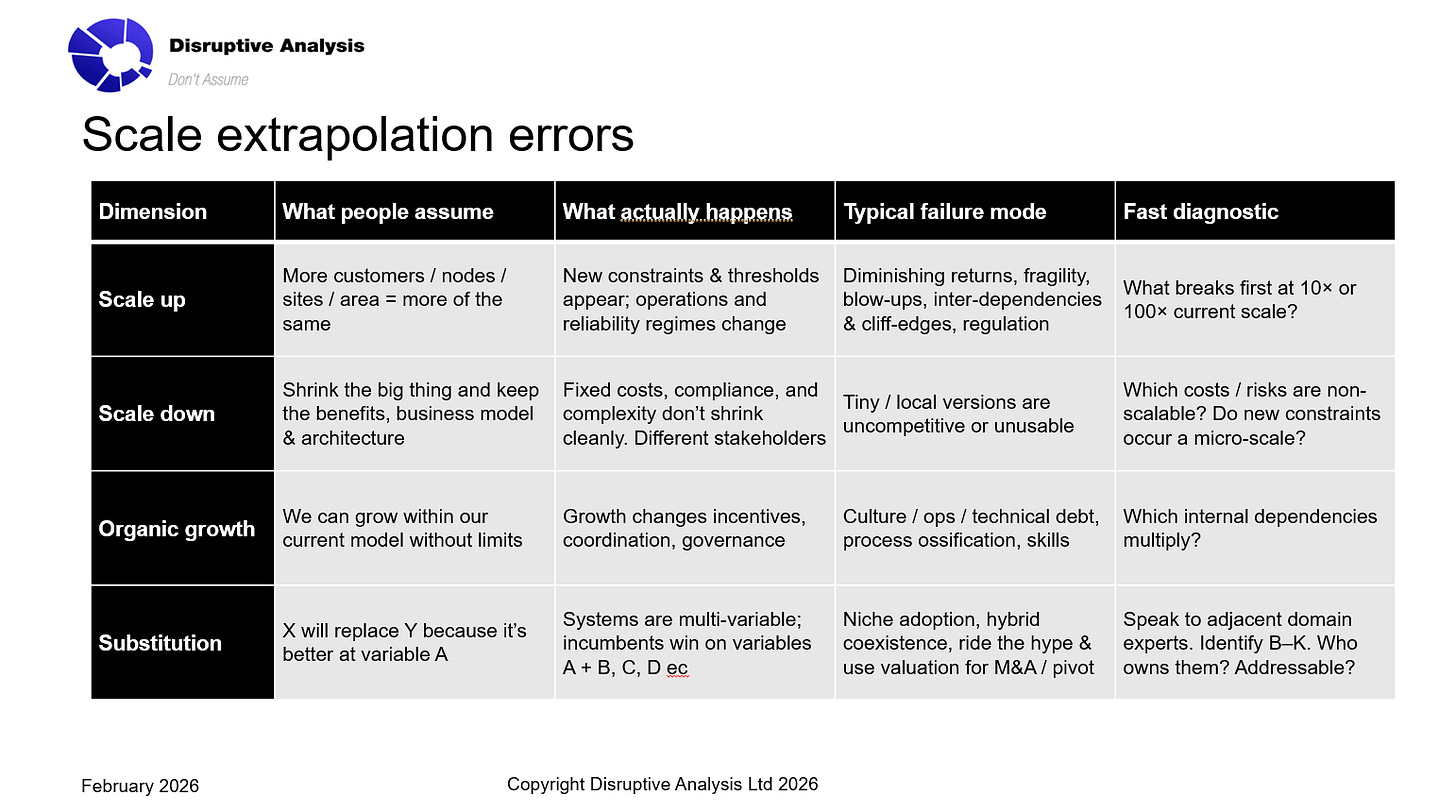

The four classes of scale extrapolation

It’s worth a brief outline of the four sub-classes of error here, plus some examples. These are all topics I could drill into more fully, or create case-studies, but it’s worth having a basic taxonomy as a starting point.

1. Scale-up organically

This is the most common internal corporate failure mode, although it is also seen in industry-wide forecasts and (sadly) a lot of analyst research.

Pattern

“We’ll replicate this success across markets/regions/segments.”

“We’ll hire salespeople / deploy sites / add SKUs and margins will follow.”

“We’ll extrapolate growth based on % of population or GDP, or invent a CAGR”

Why it fails

Coordination costs rise super-linearly, especially if you have multiple versions, customisations or integrations.

Quality and reliability targets get stricter as your product or service becomes critical infrastructure, or at least business-critical for customers.

The organisation accumulates “operational debt” in terms of processes, tooling, fragmentation, channels or skills.

Examples

A telecom operator assuming nationwide 5G rollout is just “more sites,” then discovering that site permitting, backhaul availability, indoor coverage, and energy costs start to dominate beyond certain thresholds.

A fibre network moving from a bulk build-out “homes passed” machine, to one struggling with “homes connnected”, with each building needing a different physical design, while still trying to work out what to do about MDUs and isolated homes needed to hit regulatory coverage goals.

A cloud service scaling from thousands to millions of tenants, then hitting identity, abuse, noisy neighbors, redundancy, internationalisation and compliance cliffs.

A company believing “we can add AI agents to every workflow,” then drowning in governance, model drift, security review, and integration sprawl.

2. Scale-up + Substitute

This is the example cited in the post about space datacentres. It’s a common one in telecoms and cloud sectors, especially given the prevalence of narrow domain experts and “fanboys” - for instance, observers and policymakers unaware of major “gotchas” like indoor wireless complexities, regulatory oversight or seemingly minor inputs like numbering resources.

Pattern

“Innovation X replaces incumbent Y because factor A is cheaper/faster/cleaner.”

“The new thing will kill the old thing”

Why it fails

Incumbents survive by optimising many variables (B, C, D etc), not one.

The challenger must match the incumbent’s system-wide properties, not just a single headline KPI.

At scale, your “advantage” can flip into a constraint (e.g., energy abundant but cooling impossible; bandwidth cheap but latency intolerable).

The old thing is rarely static. It’s evolving too, so you need to compare with the future version, not the legacy installed base that’s easier to upgrade.

Examples

Space datacenters replacing hyperscale DCs: Variable A: solar energy. Variables ignored: heat rejection, maintenance, interconnect, sovereignty, latency, supply chain.

Satellite D2D replacing terrestrial mobile: Variable A: coverage footprint. Variables ignored: capacity, indoor, handset power & uplink, interference, economics of cities).

“LLMs and agentic AI replace software”: Variable A: flexibility. Variables ignored: determinism, compliance, auditability, liability, predictable costs, integration, testing.

3. Scale-down organically

Rather counter-intuitively, the scale extrapolation problem occurs in both directions. Sometimes, a technology which works at “normal” scales doesn’t work in particular locations, or particular segments or niches. Scaling down, or filling in gaps, can be problematic.

Pattern

“We’ll make a small version of the large system for SMB / edge / remote”

“Our main solution will work fine for filling in the gaps”

“We’ll productise what we do internally for ourselves”

Why it fails

Fixed costs don’t shrink in the same way: compliance, support, security, audits, 24/7 operations, multi-national documentation etc.

Complexity often stays: the “small” version still needs skilled deployment, margin-hungry channels, salesperson bonuses and knowledgeable customers.

Utilisation collapses or is lumpy: small deployments can’t amortise redundancy.

Examples

In-building wireless systems (or outdoor-to-indoor) promising100% coverage including basements, stairwells, elevators

A “mini cloud region in a box” that still needs patching, monitoring, security updates, spare parts, and skilled operators.

A “lightweight 5G core” for private networks that still inherits configuration and security complexity - and MNO-grade pricing

CDN nodes intended for deployment deep into access networks, despite a low “hit rate” from a smaller number of local users.

4) Scale-down + substitute

This is the mirror image of “X replaces Y,” but with fragmentation or decentralisation rhetoric.

Pattern

“Distributed / edge / micro / peer-to-peer will displace centralised platforms.”

“Cut out the middle-men and own the capacity yourself”

Why it fails

Centralised systems often exist because they exploit economies of scale in:

coordination

reliability

security

financing

governance

Distributed systems often shift costs to the edges - which typically means individual “grass roots” administrators. Systems management, troubleshooting, integration, security are all problematic.

Boundaries are killers, especially if mobility is involved

Failing to understand overall system scope and interactions, e.g. devices vs. access network vs. core / transport vs. billing and backend systems

If the coordination burden moves from one operator to thousands of operators, it didn’t eliminate the problem; it fragmented it.

Examples

Edge compute replacing cloud. In practice, it’s a tier, not a substitute.

Blockchain-based cellular or Wi-Fi networks aiming to compete with commercial-scale ISPs or MNOs, by incentivising individual islands of deployment.

Solo contractors vs. gig-workers using a platform and common brand

Electricity microgrids replacing national grids

Local manufacturing or 3D printing “replacing” global supply chains

Conclusion and how to avoid scale extrapolation errors

In a way, scale extrapolation is something like a business and technology version of a cognitive bias. We tend to assume that something that works will work better as it grows - or perhaps shrinks. We have internalised the concept of scale economics, without stopping to think about how / where it breaks.

As this article suggests, these errors manifest in a lot of different ways. But there are a few easy check-list items to consider as a filter or test.

The question list that people should ask themselves (or a true believer) includes:

What breaks first at 10× scale? Or at 0.1x? Could be physics, operations, economics, skills, regulation etc…

Which variables become dominant at scale? This is often not the one variable in the pitch, and could in fact be a long list of technical and non-technical things.

What is fixed-cost per deployment / tenant / region? This is especially important for scaling down, but also may change in different “regime” zones for scaling up

What must be true for 99.99% coverage, reliability or availability? And what does that cost, who measures it, and what are the consequences of failure?

What does 1% / 10% / 50% adoption look like? This is especially important for replacement scenarios

Which extra stakeholders will “wake up” as you scale? What will they demand?

It’s instructive to look at companies or industries that have scaled smoothly, such as GPUs or 4G / early 5G mobile or solar energy. And then compare them with the salutary lessons, failures or perpetual niche solutions from sectors like metaverse, RCS messaging and 5G network slicing.

I’ll have more to say about scale extrapolation errors, as once you start noticing and categorising them, you’ll see them everywhere. And in many cases, they can be mitigated.

If you’re interested in exploring any of the issues in this article, or more broadly in terms of strategic developments in telecoms, AI, cloud and networking, please get in touch with me. I offer private advisory services, keynote speaking and panel moderation.

Tremendous examination. We need more common sense.